Coastal Creationism - Part 4: Sedimentary sequences and superior shapes

Why do some sections of coast get better reefs than others?

Why do some sections of coast get better reefs than others?

In previous articles we looked at what makes a good reef shape, and then what shapes on the coast - that is, the coastal features such as headlands - create good surf set-ups. In this article we look under our feet to the bedrock geology and what this means on both a regional and local level for the type of reefs and the surf they create.

The geology underlying any reef is usually part of a greater regional sequence of rocks, such as a sedimentary basin or granite provence. This means that particular geological provinces can lead to a grouping of similar reef shapes. When the elements come together you get a cluster of world class surfing destinations. Over the next few articles we will look at a few well known coasts and their waves, and then observe how this is shaped by the underlying geology.

We've already noted that good surf reefs needs to present a well-graded, convex slope to the prevailing swells. On Australia’s surfing coasts, the most likely geology to create these shapes is horizontal (or nearly horizontal) bedded sedimentary rocks. This is because the weaknesses in the rock are often along those horizontal bedding planes. Powerful swells can help shape the reef, but most importantly any shapes will be gradual; if the steps in the reef slope are equal to the thickness of each bed of sedimentary rock, then for the right thickness of bedding, the reef can form a nicely convex shape. For example, areas with gently sloping sandstones in regular, medium thickness beds seem to get excellent reefs.

The ideal shape is a nearly horizontally bedded reef of rock, eroding to broad flats in the shallows but with a steeping (convex) slope into deeper water. Essential to creating this shape is avoiding large vertical breaks or steps in the shape. These reef shapes are best found where the bedrock is nearly horizontal and of medium thickness (beds approx 0.2 metre – 1 metre thick). It helps if the beds are of relatively hard but not too blocky rocks, interspersed with thin beds of softer rock like shale.

The ideal shape is a nearly horizontally bedded reef of rock, eroding to broad flats in the shallows but with a steeping (convex) slope into deeper water. Essential to creating this shape is avoiding large vertical breaks or steps in the shape. These reef shapes are best found where the bedrock is nearly horizontal and of medium thickness (beds approx 0.2 metre – 1 metre thick). It helps if the beds are of relatively hard but not too blocky rocks, interspersed with thin beds of softer rock like shale.

The Sydney Basin is actually a sequence of sedimentary rocks stretching from Batemans Bay in the south, Newcastle in the north, and as far west as Lithgow. Although TV weather people may actually confuse the 'basin' with the Sydney Metro region which only extends to the base of the Blue Mountains. In that context it's a geographical feature, not the basin of sedimentary rocks that actually creates the name. The Sydney Basin rocks are mainly shales, sandstones, and coal measures and usually nearly horizontally bedded. The variation along the coast is in the hardness of the rocks and the thickness of the beds.

For the nerds out there, these sediments were laid down over a period from the Permian (around 250 million years ago) with shallow marine and some glacial sediments overlain by the coal forming swamps and forests. Later these were overlaid by Triassic (180 million years old) sandstones and shales of the Narrabeen and Hawkesbury Groups, laid down by large rivers spreading huge thickness of sand across broad braiding river channels. These were later buried by shales and mudstones in floodplains and lakes.

Example 1: The Sydney Basin - the good reefs

Example 1: The Sydney Basin - the good reefs

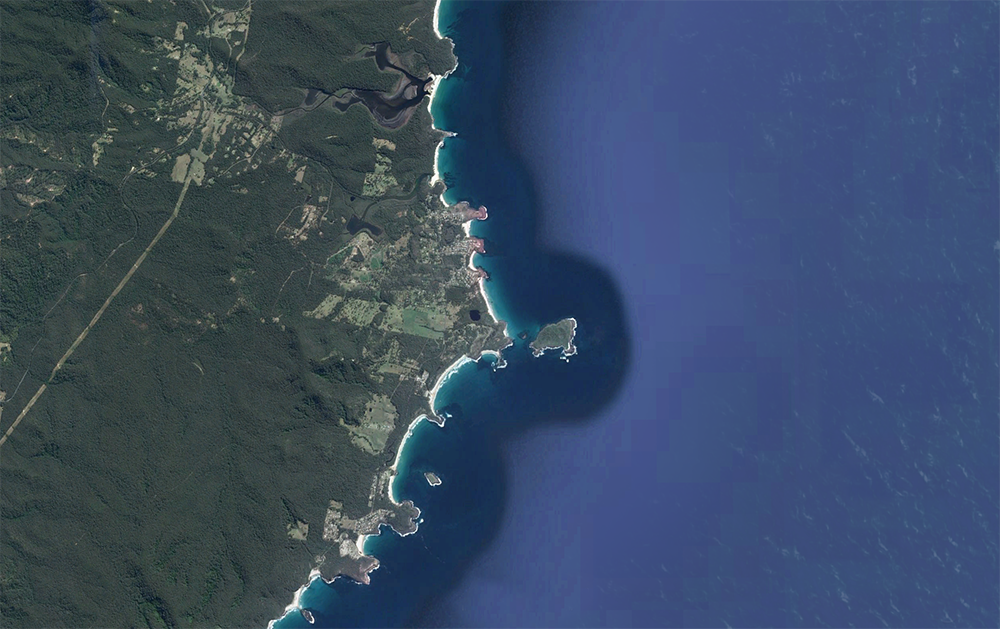

Some parts of the Sydney Basin offer a high density of good reef breaks (eg: the South Coast) whereas other parts of the Sydney Basin are characterised by paucity of reef breaks (eg: The Eastern Suburbs). Lets look at what works first. The Coal Coast, Shellharbour and Ulladulla regions offer a high density of good-to-great surfing reefs, every headland has something surfable, and sometimes epic! Some spots are truly world class and a lot of points have waves on both the north and south sides - an unusually wave rich situation. What is happening that allows almost every point to form a surfable reef?

The answer lies in the geology of the region, being mainly thinly bedded sandstones, siltstones, shales and coal seams of the Illawarra Coal Measures. All these amazing reefs are formed where horizontally bedded shales and sandstones of moderate hardness have eroded to form convex smoothly graduated reef slope.

In other parts of the Sydney Basin geology where the sandstone beds are thicker and harder then the reefs can have significant steps in their profile. For example the Cronulla Region reefs are formed by Narrabeen Group and Hawkesbury Group sandstones. These are characterised by horizontal beds of harder quartz sandstone between 0.5 metre and 3 metre thick, interspersed with thinner beds of softer siltstones, shales and mudstones. Due to the thick hard beds layered with thin soft beds, the reefs will often have abrupt steps in their profile, creating a distinct ledge. It is no accident that surfers talk about many of Sydney’s sandstone reefs as ‘ledges'. The Cronulla Region has been blessed by the fact the Hawkesbury Sandstones are not too hard or too thickly bedded. The reefs are convex, with the odd ledge or two (Shark Island anyone?).

Other regions of Australia characterised by horizontally bedded sedimentary rocks include Victoria’s Surf Coast, although the rocks are limestones and not sandstones.

Example 2: The Sydney Basin - coasts with no reefs

Example 2: The Sydney Basin - coasts with no reefs

In other parts of Sydney (eg: the Eastern Suburbs) the predominantly Hawkesbury Sandstones are too thickly bedded and blocky to form good reef breaks. From the north side of Botany Bay to North Head the coast is characterised by cliffs of blonde Hawkesbury sandstone. If you look at the profile of the cliffs, the ledges are usually 2 to 3 metres thick, and sometimes more. This situation is repeated near Jervis Bay where the hard Nowra Sandstones are too thick and hard to create good reefs. Conversely the hardness and uniformity of the Nowra Sandstones have created world class rock climbing at Nowra and Point Perpendicular.

These thick, hard sandstones extend under the sea surface and result in vertical and blocky underwater topography, hardly conducive to the well-graded covert reef profile of a good surfing reef.

It is only north of Curl Curl that the Narrabeen Group Sandstones start to outcrop once again. With more softer siltstones and shales between the sandstone beds and generally fewer thick beds of uniformly hard sandstone, the reefs are more likely to form the convex profiles and less likely to form steep blocks and steps. The Narrabeen Group rocks start to appear north of the base of the cliffs at Dee Why, hence surfable bedrock reefs at Dee Why Point and Long Reef and some half decent reefs further north

There are many different types of rocks and geologies that shape coasts. Over the next few articles we will look at some of the important characteristics of Australia’s best known surfing coasts.

Coastal Creationsim is an eight part series written by Chris Buykx. Chris is a geologist, traveller and lifelong surfer. Specialising in eco-tourism, his passion is interpreting nature and the environment. Chris is a resident of Sydney’s Northern Beaches though he's currently doing a lap of Australia with his family. Read past articles:

Part 1: Basic reef shapes

Part 2: Complex curves

Part 3: The good, the bad, and the ugly of coasts

Comments

Fantastic. This stuff fascinates me. Often wonder why a headland sticking out on Google maps that looks like it should be a sweet right hander barely corresponds to a breaking wave when you actually get there. Keep it coming.

And an area with volcanic basalt has only short sharp peaks or clunky walls e.g.. Flinders and to a lesser extent PI.

I share the enthusiasm of other commenters in this series, it's great reading. Today's article has got me thinking......if horizontal beds make for good reefs then I'm assuming the opposite is true and angled beds make for bad reefs?? Would this explain the Forster to Seal Rocks section of coast which has rock shelves exposed at sharp angles and no reefs?

Yeah, same around the Victor Harbor region, from The Bluff further around to Cape Jervis, just sharp angled rock/reef which is too abrupt for any decent surf.

Absolutely correct Atticus. The near vertical bedding of the folded sequences north of Seal Rocks or especially south of Batemans Bay show how it is almost impossible to form good reef shapes in this type of geology. In these situations the only surf options are either boulder points or beach breaks

Thanks Chris.

Imagine this titled 90+ degrees back the other way!

Base of Tassie has a bit of this as well.

Basalt column headland from Gondwana super volcano.

Lava extrusion on Basalt vertical hexagonal column headland .

Man made prawn.

Hahahaha :)

One of places where the geological/surfing connection really stands out for me is the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula, with all the limestones / dune deposits. Lots of nearly-horizontal strata that seems to cut readily into wide shallow reefs. Kinda has the feel of coral at times.

Granite coasts are usually not that great. Shapes are formed deep in the earth without much refrence to horizontal. Granite coasts have bombies more than reefs and boulder strewn points are rare. Usually they just go deep quickly and you have to rely on beach breaks.

Dolorite is not ideal and usually shelves too fast into deep water but with more gentle slopes it does tend to weather into boulders at the base of headlands that can become boulder strewn points with some help from sand.

Drowned Glaciated coasts can be too deep too quickly - southern Tassie.

The type of sand also has an impact on beach breaks. Course sand seems to allow deeper channels compared to fine quartz from granite coasts.

Wait for Coastal Creationism #6 for my take on granitic coasts. Although I am thinking I may need to do an additional analysis on those coasts where young limestones overlay ancient granites. The most epic surf regions (Margaret River, Cactus and Eyre Peninsula) all seem to limestone reefs sitting on top of granitic domes. I suspect there is relationship between the granitic dome forming a good platform for the accumulation of shallow marine sands that become limestones at times of low sea level. When sea level comes up to our current high-stands there is bunch of well shaped and positioned limestone bodies to form good reefs.

I only bother to read when freeride76 (sic) bothers to comment.

One interesting phase in history to think about is around 3/4 of the way to current sea levels after the last ice age. Around Australia many, many beaches that now stretch between headlands would have been partially formed with sandbars and shoals linking the headlands often with a channel opening into a lagoon behind the newly forming beach. There would hav e been so many setups peeling off the headlands into the deep water lagoon mouths that would have been a common feture on most beaches. Only a few such channels now exist as sand has fillled the gaps.

I think there is potential for a whole book on sand. At this stage reefs are easier because they don't move very quickly.

The way sand has been deposited on coastal plains during low sea levels and what happens to that sand at higher sea levels varies massively on different parts of the Australian coast. The infilling of drowned valleys such as the Sydney region is a whole other story on top of that. I will have to build it in to coming articles

As an aside - Is the last picture in the article of the coast immediately adjacent to Waverly cemetary? Cause I've often noticed a completely inaccesable poor-mans Our's there on bigger swells

I don't know the wave off Waverly Cemetery, however I suspect it may be cliff base boulder field. These breaks tend only show in the bigger swells and are formed by giant boulders from cliff collapse forming in to a workable reef shape. Deadmans and even Fairy Bower at Manly have formed in this way

great series - Chris can you please do an article on cliff side boulder fields too.

I have noticed how many of them have the huge blockish boulders further out the point, and as you get closer to shore, the boulders become smaller and more rounded, all from wave-action I suspect, I am thinking Bronte and Bower and several more boulder reef/points in Sydney. Is this sorting a 10,000 year process? or shorter or longer?

awesome. thanks

How about the north side of Long Reef? A lot of flat bedded clay/siltstones, some thin sandstones, and by rights there should be an epic right hander peeling down towards fishermans in a decent swell.

Has to do with the dip?

Good comment Tootr. Near horizontally bedded sediments do form good surfing reefs - but not every point and not all perfect. The reef shape is also governed by the topography existing before the sea level rise as well as a multitude of other factors. However Longreef has more surf able reef breaks than you realise and certainly more than any other point that i can think of. The are at least 6 breaks from Butterbox around to the Boat Ramp. Admittedly none are world class but they have their days. The rights of the NE tip are called Chins or outer Makaha and are certainly surf able but more popular with the Tow and Step off crew rather than regular surfers. Interestingly the mudstones of Longreef are some of the softest rock reefs I know. The water is always brown due to the erosion of the soft mudstones

I'm really enjoying your articles, please write as many as you want!

(If you don't keep writing I will protest; by teaching all Scandinavians to surf)