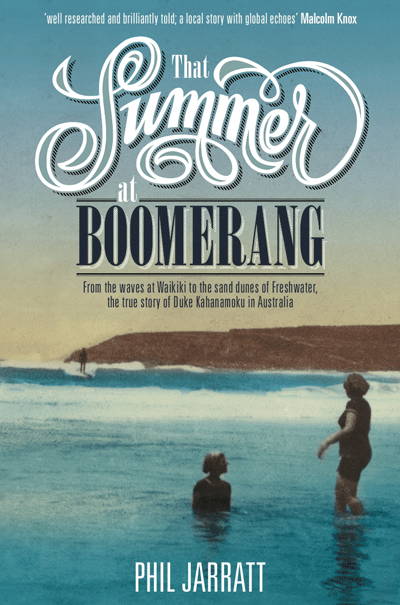

'That Summer At Boomerang' by Phil Jarratt

That Summer At Boomerang might not be quite the book for your surf crazed teenager but for those of us with a longer experience and interest in Australian surfing culture it is required reading. Phil Jarratt has put Duke Kahanamoku's famous tour into its historical and social context with an exhaustively researched account of the events and personalities surrounding it, with particular focus on Duke's relationship with Isabel Letham, the teenage girl he taught to surf at Freshwater Beach.

That Summer At Boomerang might not be quite the book for your surf crazed teenager but for those of us with a longer experience and interest in Australian surfing culture it is required reading. Phil Jarratt has put Duke Kahanamoku's famous tour into its historical and social context with an exhaustively researched account of the events and personalities surrounding it, with particular focus on Duke's relationship with Isabel Letham, the teenage girl he taught to surf at Freshwater Beach.

Those who research and write about myths always run the risk of missing the point, since the point is the myth, not the reality. Myths are constructed from the rough framework of events, thickly rendered with cultural bias. So it is always brave to embark on an exercise, as Phil Jarratt has here, likely to result in a stripping away of that render. To push the analogy a little further, a builder soon learns not to judge by appearances since they can hide the basic structure of a building. Ripping off the metaphorical render then runs the risk of exposing the myth as structurally unsound.

Although it was probably not his intention, Jarratt's text certainly provides ammunition for those with iconoclastic tendencies by revealing the extent to which Australian surfing had developed prior to Duke's tour, the power of the publicity machine that accompanied it and the exploitation of Duke's talent by his Australian promoters. But myths are nothing if not resilient. Generations of Australians have known that Gallipoli was a shambolic defeat, but it has never stopped them from celebrating it as a glorious triumph.

So it is with Duke. It is surely beyond dispute that Australian surfing was going to continue to expand, with or without the stimulus he provided. It is even debatable whether, 100 years later, he made any significant difference at all to the long term development of the sport. The myth though will survive that analysis. We need our gods and heroes and anyone doubting Duke's place in the pantheon has never stared at the statue of him erected on Freshwater headland where he stands, as he does in our mythology, so much larger than life.

The irony is that, having placed him on a pedestal, Australian surfing then largely repudiated the values that he taught. The aloha spirit and the relaxed, non-competitive style of the Waikiki beach boys never took hold in a sporting culture dominated by the narrow authoritarian attitudes of the swimming and life saving clubs and even decades later, when boardriders broke away from that culture, it was not long before similar attitudes emerged and organised surfing competition assumed an importance that would have been incomprehensible to the happy-go-lucky Hawaiian beach boys of Duke's era.

Throughout the text there is a real tension between Jarratt's obvious desire for historical accuracy and the need to entertain. It is a sustained balancing act with remarkably few wobbles along the way but it is one that inevitably subverts the desire to the need. Despite all the research and detail it is hard to look at this as a totally reliable history when, by his own admission in the Author's Note, some undefined quantity of the direct speech comes directly from his imagination. It may be that the best way to view the text is to consider it as layered. There is the historical level, the well researched level of who was where when and what they were doing. The next level might be described as the inferential level where the author draws presumably sound conclusions about the characters' interactions and opinions based on the evidence. The third level is the pure speculation of some of the direct speech.

All this is not only forgivable but a demonstration of the author's craftsmanship. A strictly historical account of these events would be a purely academic exercise. It is not possible to dramatise the limited material available without a liberal application of imagination. The characters portrayed here, walk, talk and breathe but if, at the end, you fail to be quite convinced that they are true to their actual personalities, then you are still left with that underlying level of factual reporting upon which you can place your own interpretation.

The story of Duke also raises the spectre of the cultural cringe; the concept that the native Australian product can never match the best of other cultures. Why else would we ignore Tommy Walker's achievements and idolise Duke? Not just then, but ever since. If we are really interested in the development of Australian surfing surely the story of the merchant seaman who bought a board in Hawaii, surfed up and down the NSW coastline for years before Duke arrived and who was acclaimed as our best surfer of the era, is of at least equal significance. But there is no statue of him on a prominent headland and his name remains virtually unknown.

The open, non-judgemental style he has adopted restricts Jarratt's ability to directly address some of the more controversial issues raised by the story. The Australian culture of the time was racist and sexist. It allowed already wealthy men to benefit from Duke's achievements while he himself received no financial benefits at all. These are not side issues they are central to the story and its aftermath. Then there was the split-level hypocrisy: that of the white elite in celebrating Duke when they had only recently deported, after years of indentured labour, some of his fellow Polynesians, and that of Duke himself in being prepared to be treated as an honorary white.

Whatever you think of the myth or of Duke himself, this book does us a great service in collecting everything known about these events into a single well referenced text. It is a great achievement to not only have marshalled the research into an entertaining text but also to have produced one that allows the reader an opportunity to place their own interpretation on the events described. //blindboy

That Summer At Boomerang is published by Hardie Grant and retails for $29.95.

Comments

"The irony is that, having placed him on a pedestal, Australian surfing then largely repudiated the values that he taught. The aloha spirit and the relaxed, non-competitive style of the Waikiki beach boys never took hold in a sporting culture dominated by the narrow authoritarian attitudes of the swimming and life saving clubs "

Great point BB. It was something I was thinking about recently when reading an article on the Duke's legacy here in Oz. Funny isn't it? He didn't 'bring' surfing to Australia, and he didn't teach us any values that stuck, yet we're still in awe of him.

I read it and, like BB, also noted the inferred conversations. At first it passed me by till I began wondering how conversations from over 100 years ago were recorded. Yeah, slow on the uptake I know.

At times it bugged me but, like BB says, I'll put that down to "the tension between Jarratt's obvious desire for historical accuracy and the need to entertain." After I finished the book I read the Author's Note where Phil explains and justifies the imagined conversations. Probably should have read that bit first.

"Australian surfing then largely repudiated the values that he taught. The aloha spirit and the relaxed, non-competitive style of the Waikiki beach boys never took hold"

This is an interesting point and alludes to another great Australian cultural myth of identity, the identity of being "easy going". Nowhere is this myth exposed more than in the country's attitude toward sport. Known the world over for how competitive we are across the sporting arena, yet we perpetuate this myth of the easy going Aussie. Fantastic writing!

Thanks silicun, I think there is, or maybe used to be, an easy going streak in our national character, that "she'll be right" feeling. My own hypothesis is that, since it doesn't occur in the Irish or English, it came from indigenous culture. uplift may correct me there if I am being presumptuous.

Our competitive sporting culture, I think, came very much from England and was intensified by our insecurity about our national identity. For much of its history Australia has not been able to compete economically or politically with the major powers so we put a huge cultural emphasis on sport where we had the natural advantages of climate and space.

Really nice review BB.

I don't always agree with you, but it's always a pleasure to read a well written piece with a cogent thought out premise and accompanying argument.

Interesting how the nascent surf culture was hijacked by that super hierarchical, authoritarian surf club movement which, according to the accounts I've read and been told about, was quite the social ladder for Sydney society.

Guess, nothing much has changed eh.

Agree with freeride76. Great review. I believe BB should get a gig at the Byron Bay Writers Festival or high school English teachers invite BB to some of their classes to engage students in their literacy learning at HSC level.

Who is Tommy Walker?

Has anyone researched this guy? Does he have a good story to tell?

Thanks for the compliments finback. Reecen, I had heard of Tommy Walker before reading Boomerang but I would be pretty sure that Phil Jarratt did a thorough job of research for the book so I am not sure there is much more to learn. He was a seaman who bought a board off the beach boys at Waikiki, brought it back to Australia then, as he worked the coastal trade, surfed up and down the east coast, most notably Yamba where he was based for a while. At the time of Duke's tour he was known as the best local surfer.

Cheers blindboy,

I should read the book then.

BB has reflected an exceptional abstract. Sound in thought and fair in appraisal. We, as the current generation, embrace questioning and the validity of currency of mythology. And rightly so. We have in our life time seen such change that those before us may not have believed possible only a few years ago (think Hitchens taking on the Church will loaded six shooters on each hip).

Mythology is often prolonged when fear of the institution and/or ignorance of the facts are failed to be tackled. BB's address of the 'native product' is a valid case of note. Tommy Walker, among others but more readily known, should fairly be up there.

Can I though address what we should celebrate. That is the warmth of a dark skinned man, in a time of white Australia, bringing Aloha with him that made an indelible impact on all those who met Duke. It is this Aloha that we should recognise as the strength of Duke's visit and his gift to us. A smile and warmth goes a long way, in particular when being called into a nice westside Makaha swell.

Not doing much this weekend? Make your way to Freshie and hear Phil Friday night. I think it will be worth it.

http://www.pacificlongboarder.com/news.asp?id=5279&category=1

Aloha.

......might just do that u-turn.

say G'day. I'll be the bloke introducing Phil & Chuck.