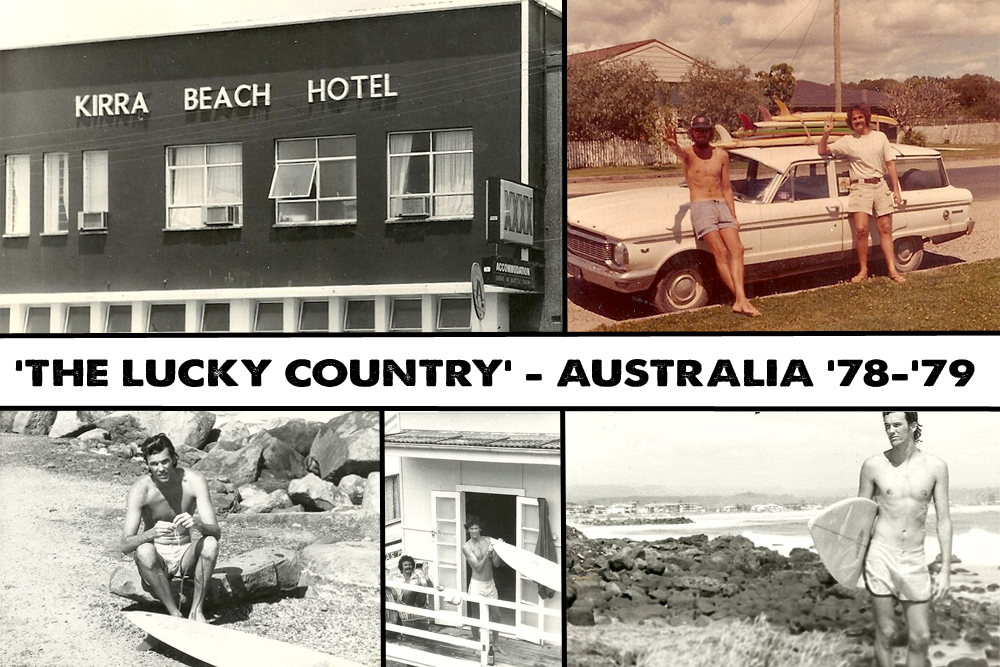

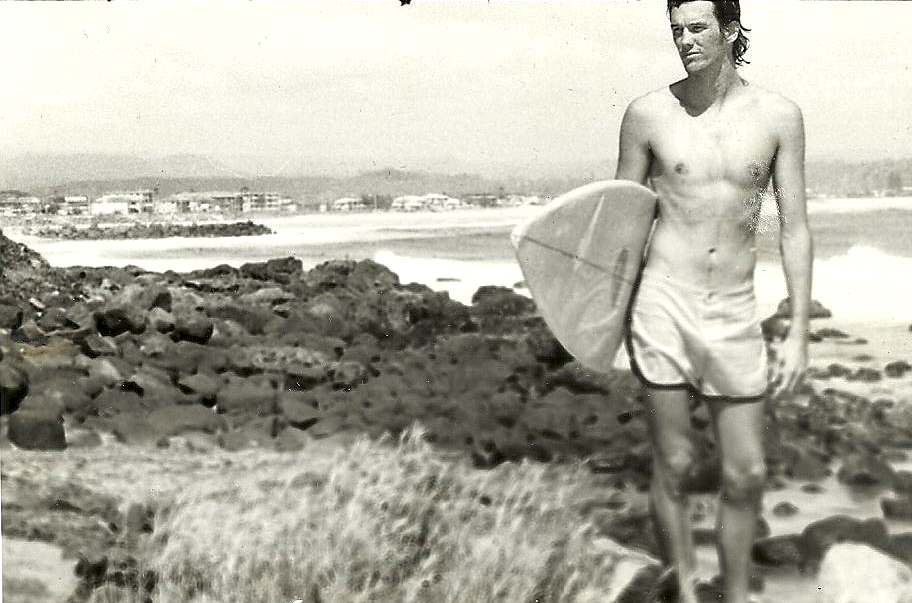

After many months in the South Pacific, living out of knapsacks, camping, and looking for waves, Bryan Di Salvatore and I landed in Kirra, Queensland, near the New South Wales border. We were the proud owners of a 1964 Falcon station wagon, bought near Brisbane for three hundred dollars. First we car-camped and surfed up and down the coast, from Sydney to Noosa. It was dazzling to be back in the West, with all its comforts and conveniences, and to be surfing known spots—there were even road signs, SURFING BEACH. It was great to have wheels. Food and gas were cheap. Still, we were nearly broke. And so we rented, with our last funds, a moldy bungalow at the back of a ramshackle complex misnamed the Bonnie View Flats. Most of our neighbors were unemployed Thursday Islanders—Melanesians, from the Torres Strait, up near Papua New Guinea—and some of them possibly had views. We certainly didn’t. But the beach was just across the road, and we had not chosen Kirra randomly. The place had a legendary wave. And the southern summer was starting up and, with it, we hoped, northeast cyclone swells.

Bryan got a job as a chef in a Mexican restaurant in Coolangatta, the next town south. He told the owners he was half-Mexican, but fumbled it when they asked his name. He said McKnight when he meant to say Rodriguez. He didn’t have a valid work visa under any name. They hired him anyway. I found a couple of backbreaking jobs, including ditchdigging, which deserves its reputation as the worst sort of donkey work, for cash paid daily. Then I got hired as a pot washer in a restaurant at the Twin Towns Services Club, a big casino just over the New South border, fifteen minutes’ walk from our place. I told them my name was Fitzpatrick. The manager said that as a condition of employment I had to shave my beard, and so I did. When Bryan came home that night, he took one look at me and shrieked. He looked genuinely distressed. He said it looked like half my face had been burned off. I was pale where the beard had been, dark brown everywhere else.

There, there, I said, it’ll grow back. This was actually sweet revenge because Bryan had dogged me for ages about my moth-eaten excuse for a beard. “It looks really good, Bill,” he would say. “You look like a really liberal priest.” He didn’t mean that as a compliment.

I blew my first wages on surfboards. Kirra is on the Gold Coast, a surfing center, and there were cheap used boards everywhere. I bought two, including a 6'3" Hot Buttered squashtail that turned on a dime and, when necessary, went outlandishly fast. It was a sports car of a surfboard, and a nice change after months of riding my sturdy travel board. Bryan also got new, much smaller boards. The year-round neighborhood spot was called Duranbah. It was a wide-open beachbreak immediately north of the Tweed River mouth, very near my casino job. Duranbah always seemed to have waves. They were often sloppy, but there were gems scattered among the mush. On my twenty-sixth birthday, I got a sweet barrel on a shining right and came out dry.

The pointbreaks—Kirra, Greenmount, Snapper Rocks, and Burleigh Heads, the spots that put the Gold Coast on the world surfing map—would light up after Christmas, people said. They would start breaking, in fact, on Boxing Day, December 26, we were assured by a nonsurfing neighbor. We laughed at the not-likely specificity but looked forward to the waves.

In the meantime, I was falling hard for Australia. The country had never interested me. From a distance, it always seemed terminally bland. Up close, though, it was a nation of wisenheimers, smart-mouthed diggers with no respect for authority. The other pot washers at the casino, for instance—they called us dixie bashers—were a weirdly proud crew. In a big restaurant kitchen, we were at the bottom of the job ladder, below the dishwashers, who were all women. We peeled potatoes (which we called idahos), handled the garbage, did the nastiest scrubbing, and hosed down the greasy floors with hot water at the end of the night. And yet we made an excellent wage (I could save more than half my earnings) and, as employees, we had entree to the casino’s private members’ bar, which was on the top floor of the building. We would troop up there after work, tired and ripe, and throw back pints among what passed for high rollers on the Gold Coast. Once or twice, my coworkers spotted the owner of the casino in there. They called him a rich bastard and he, properly chagrined to be rich, bought the next shout.

I had never seen the dignity of labor upheld so doughtily. Australia was easily the most democratic country I had seen. The usual class markers from other places seemed wonderfully scrambled. Billy McCarthy, one of my fellow dixie bashers, was hale, well-spoken, forty, married with a couple of kids. I quizzed him one night over beers and learned that he had been a professional saxophonist in Sydney, with a day job as a foreman in a perfume factory. He had followed his parents to the Gold Coast, where he went into business with a friend mowing lawns and washing windows, growing bonsai plants to sell at flea markets, potting palms to sell on consignment at shops. He was still working as a nurseryman but needed the steady restaurant wage. He played golf, often with musicians up from Sydney to play the casino’s nightclub or other local venues. If Billy felt embarrassed to be working as a kitchen hand, I could not detect it. He was hardworking, cheerful, politically conservative, usually whistling some corny tune, always ready with a quip. Effortlessly, he made me feel welcome. Once, as I was coming into work, I heard him call out, “There he is, the man they couldn’t shoot, root, or electrocute.”

The head chef, meanwhile, called me “Fitzie,” to which I always failed, suspiciously, to respond. The chef was the boss in the kitchen. When I once gave him shit about a garishly decorated fish being sent out, he glowered at me and said, “Don’t come the raw prawn with me, cobber.” I couldn’t tell if I had gone too far. But McCarthy and the other dixie bashers got a kick out of the exchange. They took to calling me Raw Prawn.

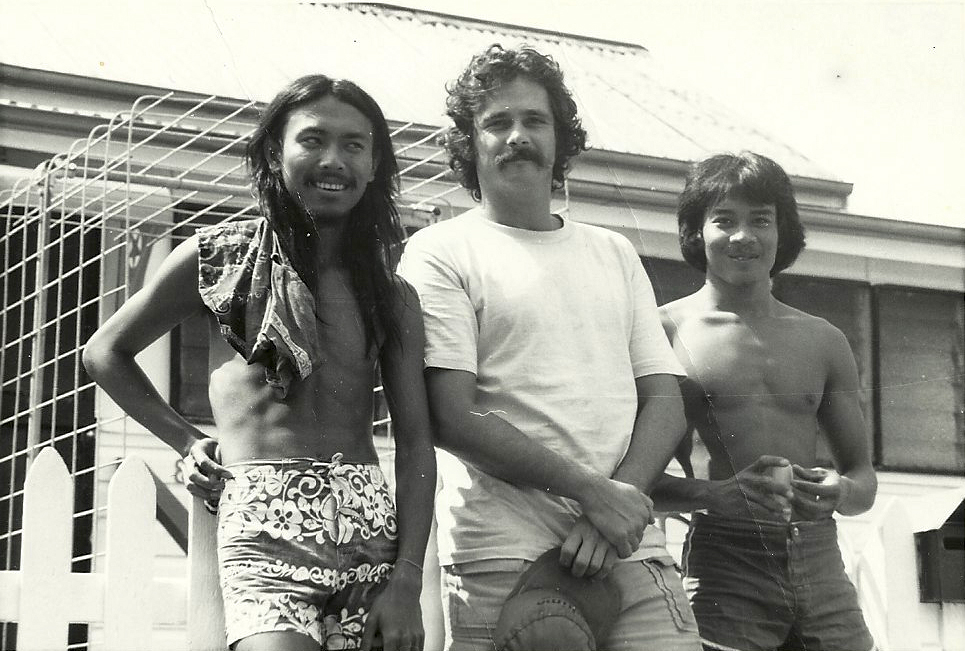

Local surfers were less welcoming. There were thousands of them. The ability level was high, the competition for waves acute. Like anywhere, each spot had its crew, its stars, its old lions. But there were full-blown clubs and cliques and family dynasties in every Gold Coast beach town—Coolangatta, Kirra, Burleigh. There were also hordes of tourists and day trippers, and Bryan and I would be assumed to belong to that low stratum of surf life until we could establish otherwise. The guys we began surfing with regularly were fellow expats—an Englishman we called Peter the Pom, a Balinese kid named Adi. One night I took Adi and his cousin, Chook, to a drive-in to see Car Wash. Chook had hair down to his waist and was the skinniest grown man I’d ever met—“chook” is Aussie slang for chicken. He and Adi got drunk on sparkling wine and laughed themselves sick at the movie, which they called Wash Car. They thought African Americans, whom they called Negroes, were the funniest people on earth.

Comments

A wonderful read.

Great start to the day.

Agreed Zen. More of this kind of content Swellnet. It's wonderful.

Good read for us old buggers … hah, the good ol times !

Well it sounds like a different world to us 'young buggers'. I think I was born in the wrong generation.

How great is the exchange with MP? "Bobby!"

And then using the mistaken identity to get more sets!

Thats well written and i want to read more. Me and two mates were camped behind Broken Head in '79 surfing nice but average waves for months but went home just before Christmas and after reading that I realise that was one of bigger mistakes we made.

Have you read the whole book Nettle? Is it all as good as that??

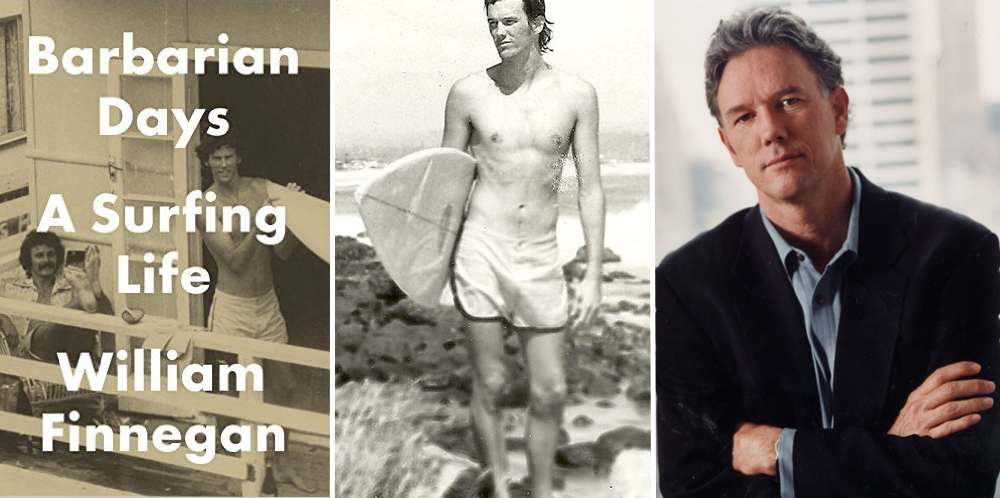

Well it's all written in the same style. That being, a very observational technique with little or no indulgences into conceptual thinking. Finnegan rarely lets you into his secret garden. However, his language and expression is crystalline clear, which compels you to keep reading, and add that to his Forrest Gump life - early days at Hawaii, discovering Tavarua, Kirra with MP, Jardim do Mar before the breakwall - and you can expect to lose a few nights curled up in bed, book on lap, with the clock on the wrong side of midnight.

My favourite chapter was Madeira and his last burst of surfing gluttony before middle age slowed him down.

Yes strange style almost stilted at times not flowing and stripped to the absolute basics. Does tell a good yarn though painting the picture well producing a page turner. I was 19 surfing Broken Head in the Spring of 1979 and MR came out one day and it was similar to how he talks about MP. MR didn't say a word just caught some great waves and put on a tube clinic with what is now his retro twinnie. Different on shore though all smiles and friendly whilst getting mobbed.

Just bought this for Father's Day and having it sent directly to Pops. Might have to get a copy for myself. When was he there? There's a certain hollow right point he must've surfed before it got fucked up by breakwalls and backwash. Jardim was only last decade.

The Madeira chapter is called Basso Profundo and begins with his first trip in 1995, continuing for ten years with a trip a year. He stays in the village at Jardim and mainly surfs there, including some mighty sessions - caught in a rising swell and fading light etc.. Also explains the breakwall fuck up from a different perspective than the Save Our Waves doco; how the island was awash with EU money and the historically poor islanders just went a bit loopy with it.

I have read the whole thing and yes it is all that good. Even better in parts.

Not sure about you BB, but after I'd finished reading I kinda wished Finnegan had taken a few internal digressions along the way. A bit of chin-stroking, done by the right person, can be a wonderful thing.

Stu, have a listen to this.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/latenightlive/riding-the-wa...

Hey cheers Whaaat. Not sure how I missed that, Aunty-loving lefty that I am.

Phillip Adams talks surfing?

It's like all my christmases have come at once!

I agree Stu, a little bit more personal insight would have helped. He must have enough material for a much more substantial memoir so maybe he is saving it for that. He is also a New Yorker writer and that kind of detached observational style is their hallmark. For me one of the best things about the book is his dual insider/outsider status. He is deeply involved in surfing and has insights that only a life-long surfer could have, yet he has also lived completely other lives as a war correspondent and professional writer. This makes him ideally suited to get it right in explaining surfing to a non-surfing audience. It is also really rare to read anything about surfing in which its absolute superiority to any other activity ever indulged in by humankind is not taken for granted. The only thing I could quibble with in the whole book is his characterisation of surfing being completely accepted by wider Australian society. By ’78 some progress had been made, for better or worse, in that direction, but if he had arrived only a few years earlier he would have found that Australian attitudes were very similar to the negative ones he knew in the US. We were long haired bums or hippies or whatever who drew immediate suspicion, if not outright abuse, in many situations. We were also targets for heavy handed policing in many country towns. Driving around with surfboards on top the car was an invitation to be booked!

It also suffered slightly by being read directly after the profoundly serious Ta Nehasi Coates book "Between The World And Me" in which he so thoroughly takes down white American culture that it was hard to see Finnegan (and by extension all of us) as anything other than a perfect example of that "white dream" culture.

BB, he touches on his first world guilt while surfing in third world countries in the RN interview referenced earlier.

sic!! forrrest gump indeed.

A touch of home fills my head with the groin take-off and the concrete floor of the Patch.

Good read. Really enjoyed the book, agree with Stu and BB : that cool observational style could have dug a bit deeper at times, but oh well, not everyone is as articulate as us convict scum.

btw, poor cunt looked like he'd just escaped the Cambodian Killing fields. Hadn't he heard of pizza and beer?

Best read I've had in a long time.

Cheers Swellnet.

Be getting hold of a copy of that immediately.

"The only thing I could quibble with in the whole book is his characterisation of surfing being completely accepted by wider Australian society."

It must have been a very bold move for a company like Coke to sponsor a major event in Sydney?

Coke had picked up on the growing influence of surfing in youth culture which was where their market was. Acceptance of surfing and surfers was far greater among young people, though there were some you had to watch out for! From memory Coke had already produced large billboards featuring surfing before sponsoring the event. My take has always been that Coke got far more out of surfing than surfing ever got out of Coke.

I see and agree.

Remember when Ampol sponsored surfing? At least surfing contests!

I think we all have stories about the Goldy, in 88 hanging with the boys from Cronulla who were staying all 8 of them it seemed in a unit behind the KB Hotel, 20 + sticks piled up on the front balcony some good some not but a lot of toast all the same, Thursday night Patch night $1 drinks hell hangovers crazy hot gals, driving from Nimbin on the back roads there then driving home the same way everyone asleep cept me, that was a tough drive, I never smashed thank god thank Mt Warning maybe, fond memories, hope all you boys are still alive and smiling, be cool bro's........

Thanks Blindboy for the insight. Ampol and Coke? Also BB, was this the period when people were joining the "special club" ?

The 2016 Pulitzer Prize was just announced with Barbarian Days winning first place for autobiography:

http://www.pulitzer.org/winners/william-finnegan

Such an incredible book, and absolute pleasure to read. Thanks for the heads up!

After that excerpt and from the glowing praise above, just bought it then.

Gonna put Cormac McCarthy on hold Stu.

Best short read in a long while. Off to the bookshop tomorrow!

New Yorker have just put up the original 1992 piece that ultimately developed into the book.

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1992/08/24/playing-docs-games-part-one

I just finished this. I don't read much for fun because I spend so much time at work in silent critical thought (and vocal critical debate for that matter), that sitting down with a book to specifically stay in my head is generally the last thing I want to do. Nonetheless, my wife mentioned the book to me when it came out as it popped up in her kindle list and she'd read the first chapter or two. I said I'd get to it because there was a buzz on Swellnet too. Finally, I had a decent spell of free time a few weeks ago so I bought it and got started. I'm glad I did, it was a brilliant read. A life so thoroughly well lived and extremely relatable that it made me question my own choices throughout. I mean, who hasn't looked over a map of the world and pondered the remaining relatively uncharted coastlines? Uncharted from a surf perspective I mean. Why haven't I followed that impulse the way Finnegan did? So many of the places I dreamed about visiting 20 and even 10 years ago are now showing up on clips on the internet.

That kind of critical self-analysis and comparison seems to be a part of my character and I think that is part of why reading isn't something I seek for solace and free time. It's a perfect cue for me to dive into that kind of thinking, and while it can be extremely positive to do that, it can also lead me down rabbit holes that might be best left unexplored.

In his review of the book , blindboy wrote that Finnegan will be the most important writer on surfing. I have certainly never read a better description of the experience of riding a wave than in this book. But I disagree that Finnegan will be seen as an important "surf writer". I don't think the book is particularly important as a surf publication. I found it to be an incredibly personal tale that coincidentally focused on surfing because of who he is not because of what surfing is. The book was about him and surfing happened to be the context. I think it would have been little different if he'd been raised in Colorado and Utah and happened to ski. His travels would have been back country missions to the Himalayas, or some other far flung mountain range, rather than the extended tropical jaunt across the Pacific and Indo, but his personal journey the same. Clearly we can't separate him from surfing but I'm using the different context to try and make the point I found surfing to be incidental to the story in the book.

And what a story, and what a story teller he is. I really enjoyed the read but to me it was incredibly melancholy, right from the start. There were times when I had to put it down for several days because I couldn't take more of the bleak tone without a break for myself. But it was so spare it left him the freedom to explore his own growth and experience in quite a sincere and masculine way. I absolutely loved that.

I'm still not sure if I was imagining the melancholy, imposing my own narrative or something, but then I read what I think are the most important words in the book that reveal what I see as the principal theme. One honest sentence, truly deserving its own paragraph:

YOU HAVE TO HATE how the world goes on.

Can't we all relate to that sometimes? I found something in every section that clicked with my own journey through life so far even though it no way resembles Finnegan's, I haven't surfed anything approaching 10 feet Hawaiian and he must be about 25 years my senior. As corny as it sounds, after finishing the book today, I wanted to meet the man, shake his hand, say well done and thanks.

Benski, I agree with your observation on his melancholy. While prone to it myself, I definitely don't think you imagined it.

A few quick words about his prose: there is so much hype, so much overstated guff and 'content' thrown at us these days, and I find it liberating to read spare, even bleak, prose like Finnegan's.

Geez, I didn't get the 'melancholy' feel as you mention. It may be the age difference, as you suggest. But he did articulate the mood and feel of the day pretty well, very well. Sure his book was personal but be sure he articulated well the feeling of a surfer in that era.

This is one of the best books I've ever read.